3D Deep Learning with Pytorch3D [Part 1 - Introduction]

Setup environment

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

conda create -n dl3d python=3.7

conda activate dl3d

conda install pytorch torchvision torchaudio cudatoolkit-11.1 -c pytorch -c nvidia

conda install pytorch3d -c pytorch3d

conda install -c open3d-admin open3d

pip install -U scikit-learn scipy matplotlib

I. 3D data processing

1. 3D data representation

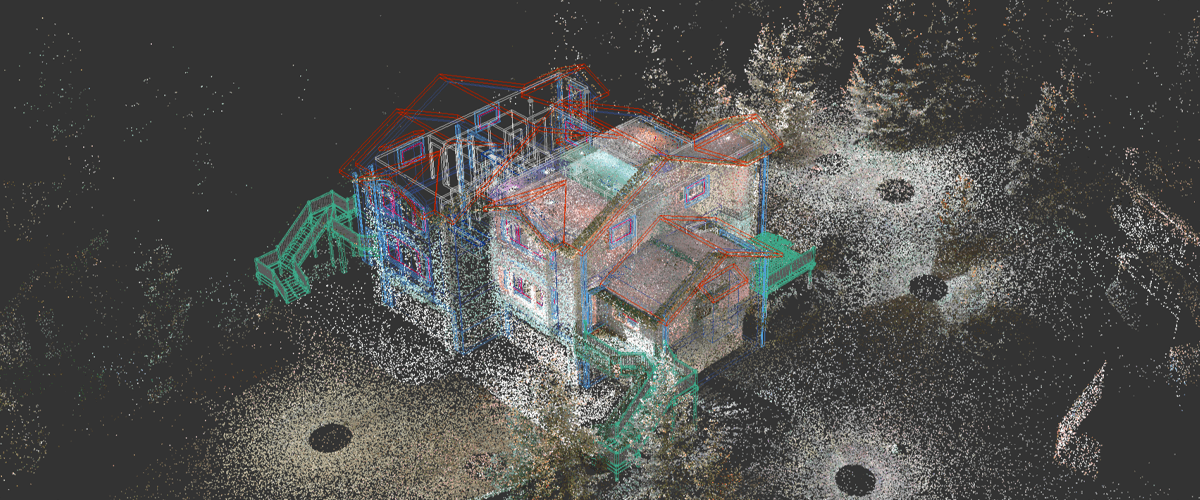

1.1. Point cloud representation

A 3D point cloud is a very straightforward representation of 3D objects, where each point cloud is just a collection of 3D points, and each 3D point is represented by one three-dimensional tuple (x, y, or z). The raw measurements of many depth cameras are usually 3D point clouds.

From a deep learning point of view, 3D point clouds are one of the unordered and irregular data types. Unlike regular images, where we can define neighboring pixels for each individual pixel, there are no clear and regular definitions for neighboring points for each point in a point cloud – that is, convolutions usually cannot be applied to point clouds.

Another issue for point clouds as training data for 3D deep learning is the heterogeneous data issue – that is, for one training dataset, different point clouds may contain different numbers of 3D points. One approach for avoiding such a heterogeneous data issue is forcing all the point clouds to have the same number of points. However, this may not be always possible – for example, the number of points returned by depth cameras may be different from frame to frame.

The heterogeneous data may create some difficulties for mini-batch gradient descent in training deep learning models. Most deep learning frameworks assume that each mini-batch contains training examples of the same size and dimensions. Such homogeneous data is preferred because it can be most efficiently processed by modern parallel processing hardware, such as GPUs. Handling heterogeneous mini-batches in an efficient way needs some additional work.

1.2. Mesh representation

Meshes are another widely used 3D data representation. Like points in point clouds, each mesh contains a set of 3D points called vertices. In addition, each mesh also contains a set of polygons called faces, which are defined on vertices.

In most data-driven applications, meshes are a result of post-processing from raw measurements of depth cameras. Often, they are manually created during the process of 3D asset design. Compared to point clouds, meshes contain additional geometric information, encode topology, and have surface normal information. This additional information becomes especially useful in training learning models. For example, graph convolutional neural networks usually treat meshes as graphs and define convolutional operations using the vertex neighboring information.

Just like point clouds, meshes also have similar heterogeneous data issues.

1.3. Voxel representation

Another important 3D data representation is voxel representation. A voxel is the counterpart of a pixel in 3D computer vision. A pixel is defined by dividing a rectangle in 2D into smaller rectangles and each small rectangle is one pixel. Similarly, a voxel is defined by dividing a 3D cube into smaller-sized cubes and each cube is called one voxel.

Voxel representations usually use Truncated Signed Distance Functions (TSDFs) to represent 3D surfaces. A Signed Distance Function (SDF) can be defined at each voxel as the (signed) distance between the center of the voxel to the closest point on the surface. A positive sign in an SDF indicates that the voxel center is outside an object. The only difference between a TSDF and an SDF is that the values of a TSDF are truncated, such that the values of a TSDF always range from -1 to +1.

Unlike point clouds and meshes, voxel representation is ordered and regular. This property is like pixels in images and enables the use of convolutional filters in deep learning models. One potential disadvantage of voxel representation is that it usually requires more computer memory, but this can be reduced by using techniques such as hashing. Nevertheless, voxel representation is an important 3D data representation.

There are 3D data representations other than the ones mentioned here. For example, multi-view representations use multiple images taken from different viewpoints to represent a 3D scene. RGB-D representations use an additional depth channel to represent a 3D scene. However, in this book, we will not be diving too deep into these 3D representations. Now that we have learned the basics of 3D data representations, we will dive into a few commonly used file formats for point clouds and meshes.

2. 3D data file formats

2.1. Ply files

The PLY file format is one of the most commonly used file formats for point clouds and meshes. It is a simple file format that can be easily parsed by most programming languages. The PLY file format is a text-based file format, which means that it is human-readable. The following is an example of a PLY file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

ply

format ascii 1.0

comment created for something

element vertex 8

property float32 x

property float32 y

property float32 z

element face 12

property list uint8 int32 vertex_indices

end_header

-1 -1 -1

1 -1 -1

1 1 -1

-1 1 -1

-1 -1 1

1 -1 1

1 1 1

-1 1 1

3 0 1 2

3 5 4 7

3 6 2 1

3 3 7 4

3 7 3 2

3 5 1 0

3 0 2 3

3 5 7 6

3 6 1 5

3 3 4 0

3 7 2 6

3 5 0 4

2.2. Obj files

Obj files are another commonly used file format for meshes. They are also text-based and human-readable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

ply

format ascii 1.0

comment created for something

element vertex 8

property float32 x

property float32 y

property float32 z

element face 12

property list uint8 int32 vertex_indices

end_header

-1 -1 -1

1 -1 -1

1 1 -1

-1 1 -1

-1 -1 1

1 -1 1

1 1 1

-1 1 1

3 0 1 2

3 5 4 7

3 6 2 1

3 3 7 4

3 7 3 2

3 5 1 0

3 0 2 3

3 5 7 6

3 6 1 5

3 3 4 0

3 7 2 6

3 5 0 4

3. 3D Coordinate Systems

3.1. World coordinate system

The world coordinate system is the coordinate system that is used to represent the 3D world. It is usually defined by the 3D sensor that is used to capture the 3D data. For example, the world coordinate system of a depth camera is defined by the depth camera itself. The world coordinate system is usually defined as a right-handed coordinate system, where the x-axis points to the right, the y-axis points up, and the z-axis points forward.

3.2. Normalized device coordinate (NDC)

The normalized device coordinate (NDC) confines the volume that a camera can render. The x coordinate values in the NDC space range from -1 to +1, as do the y coordinate values. The z coordinate values range from znear to zfar, where znear is the nearest depth and zfar is the farthest depth. Any object out of this znear to zfar range would not be rendered by the camera.

Finally, the screen coordinate system is defined in terms of how the rendered images are shown on our screens. The coordinate system contains the x coordinate as the columns of the pixels, the y coordinate as the rows of the pixels, and the z coordinate corresponding to the depth of the object.

To render the 3D object correctly on our 2D screens, we need to switch between these coordinate systems.

3.3. Camera models

The orthographic cameras use orthographic projections to map objects in the 3D world to 2D images, while the perspective cameras use perspective projections to map objects in the 3D world to 2D images. The orthographic projections map objects to 2D images, disregarding the object depth. For example, just as shown in the figure, two objects with the same geometric size at different depths would be mapped to 2D images of the same size. On the other hand, in perspective projections, if an object moved far away from the camera, it would be mapped to a smaller size on the 2D images.

II. 3D Computer Vision and Geometry

1. Exploring the basic concepts of rendering, rasterization, and shading

- Rendering: is a process that takes 3D data models of the world around our camera as input and output images. It is an approximation to the physical process where images are formed in our camera in the real world. Typically, the 3D data models are meshes. In this case, rendering is usually done using ray tracing:

An example of ray tracing processing is shown in Figure above. In the example, the world model contains one 3D sphere, which is represented by a mesh model. To form the image of the 3D sphere, for each image pixel, we generate one ray, starting from the camera origin and going through the image pixel. If one ray intersects with one mesh face, then we know the mesh face can project its color to the image pixel. We also need to trace the depth of each intersection because a face with a smaller depth would occlude faces with larger depths.

Thus, the process of rendering can usually be divided into two stages – rasterization and shading.

Rasterization: The ray tracing process is a typical rasterization process – that is, the process of finding relevant geometric objects for each image pixel.

Shading: is the process of taking the outputs of the rasterization and computing the pixel value for each image pixel.

1.1. Barycentric coordinates

For each point coplanar with a mesh face, the coordinates of the point can always be written as a linear combination of the coordinates of the three vertices of the mesh face. For example, as shown in the following diagram, the point p can be written as $uA + vB + wC$ , where A, B, and C are the coordinates of the three vertices of the mesh face. Thus, we can represent each such point with the coefficients $u$, $v$, and $w$. This representation is called the barycentric coordinates of the point. For point lays within the mesh face triangle, $u + v + w = 1$ and all $u,v,w$ are positive numbers. Since barycentric coordinates define any point inside a face as a function of face vertices, we can use the same coefficients to interpolate other properties across the whole face as a function of the properties defined at the vertices of the face. For example, we can use it for shading as shown in Figure below:

1.2. Shading Models

1.2.1. Light source models

Light propagation in the real world can be a sophisticated process. Several approximations of light sources are usually used in shading to reduce computational costs:

The first assumption is ambient lighting, where we assume that there is some background light radiation after sufficient reflections, such that they usually come from all directions with almost the same amplitude at all image pixels.

Another assumption that we usually use is that some light sources can be considered point light sources. A point light source radiates lights from one single point and the radiations at all directions have the same color and amplitude.

A third assumption that we usually use is that some light sources can be modeled as directional light sources. In such a case, the light directions from the light source are identical at all the 3D spatial locations. Directional lighting is a good approximation model for cases where the light sources are far away from the rendered objects – for example, sunlight.

1.2.2. Lambertian shading model

The first physical model that we will discuss is Lambert’s cosine law. Lambertian surfaces are types of objects that are not shiny at all, such as paper, unfinished wood, and unpolished stones:

Figure above shows an example of how lights diffuse on a Lambertian surface. One basic idea of the Lambertian cosine law is that for Lambertian surfaces, the amplitude of the reflected light does not depend on the viewer’s angle, but only depends on the angle $θ$ between the surface normal and the direction of the incident light. More precisely, the intensity of the reflected light $c$ is as follows:

$c = c_{r} c_{l} cos(\theta)$

where $c_{r}$ is the amplitude of the reflected light, $c_{l}$ is the amplitude of the incident light, and $θ$ is the angle between the surface normal and the direction of the incident ligh

If we further consider the ambient light, the amplitude of the reflected light is as follows:

$c = c_{r} (c_{a} + c_{l} cos(\theta))$

where $c_{a}$ is the amplitude of the ambient light.

1.2.3. Phong shading model

For shiny surfaces, such as polished tile floors and glossy paint, the reflected light also contains a highlight component. The Phong lighting model is a frequently used model for these glossy components:

An example of the Phong lighting model is shown in Figure above. One basic principle of the Phong lighting model is that the shiny light component should be strongest in the direction of reflection of the incoming light. The component would become weaker as the angle $c$ between the direction of reflection and the viewing angle becomes larger.

More precisely, the amplitude of the shiny light component $c$ is equal to the following:

$c = c_{r} c_{l} c_{p} [cos(σ)]^p$

Here, the exponent $p$ is a parameter of the model for controlling the speed at which the shiny components attenuate when the viewing angle is away from the direction of reflection.

Finally, if we consider all three major components – ambient lighting, diffusion, and highlights – the final equation for the amplitude of light is as follows:

$c = c_{r} (c_{a} + c_{l} cos(\theta) + c_{l} c_{p} [cos(σ)]^p)$

Note that the preceding equation applies to each color component. In other words, we will have one of these equations for each color channel (red, green, and blue) with a distinct set of $c_{r}$, $c_{l}$, $c_{a}$ values.

2. Transformation and rotation

SO(3) denotes the special orthogonal group in 3D and SE(3) denotes the special Euclidean group in 3D. Informally speaking, SO(3) denotes the set of all the rotation transformations and SE(3) denotes the set of all the rigid transformations in 3D.